ENDODONTICS AND ESTHETIC DENTISTRY

ENDODONTICS AND ESTHETIC DENTISTRY - Noah Chivian, DDS, Donald E. Arens, DDS, MSD, Asgeir Sigurdsson, cand. odont., MS

I***ODUCTION

Part of the success of esthetic dentistry depends on the dentist's ability to use teeth that have pulps compromised by trauma or injury. The role of the endodontist or general dentist performing endodontic procedures is to clearly intercept or eliminate the potential for problems. An equally important role is to respond to pulpal disease after esthetic restorations have been completed.

Endodontics has clearly established its role in providing the foundation needed to rebuild the dentition to form, function, health, and esthetics. As long as there is sufficient tooth structure to restore and a healthy periodontal complex for support, root canal therapy is the treatment of choice when a pulp is diseased or compromised by restorative demands. Although regional differences in techniques and materials exist, there is general agreement within the endodontic community on principles, that is, strict adherence to the endodontic triad of microbial disinfection and control, debridement, and the sealing of the canal system. With proven and predictable success rates, dentists can include endodontically treated teeth in their esthetic restorative treatment plans with the utmost degree of confidence.

TREATMENT PLANNING

Endodontics should be incorporated into the multidisciplined treatment process when the ultimate esthetic design is being determined. Treatment sequencing can be established and painful episodes and disruption of the restorative schedule avoided if the pulpal health and any previously root canal-treated teeth are evaluated early in the planning stages. The patient should be informed that the overall treatment plan is dynamic and may change as conditions arise. It is equally important to evaluate the patient's radiographs, and if deep existing amalgam or other restorations will be redone as part of the treatment plan, the patient should be advised of future problems owing to the depth of those restorations. If, at a later time, there are complications such as an inflamed pulp or pain following final cementation, the patient has at least been forewarned. This problem is sometimes complicated by difficulty in seeing the depth of certain tooth-colored restorations.

The removal of existing restorations, excavation of decay, and paralleling of multiple abutments may require periodic reassessment and endodontic reconsideration. Sensitive teeth that do not respond to palliative measures within a reasonable period of time may require pulpectomy. There is nothing more disheartening to a patient who has completed 18 months of combined orthodontic, periodontic, and restorative treatment than to experience a "Toothache" shortly after final cementation. Although pulpal problems cannot always be predicted, a great majority can be avoided with insight, careful evaluation, and good judgment.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

The success of any reconstructive treatment plan depends on the health of the pulp, the periradicular area, and/or the quality of the existing root canal therapy of the teeth to be restored. In an effort to determine this condition, a standardized evaluating procedure should include the following:

• Communication that includes listening and recording

• Visual examination

• Periodontal probing

• Thermal tests

• Electric tests

• Cavity tests

• Periapical tests

• Percussion

• Palpation

• Bite tests

• Radiographic evaluation

History

Besides knowing the medical condition of the patient, the diagnostician should ask the patient about past dental experiences. Their desires and objectives should be clearly defined. If neglect is evident, the reasons for the neglect should be determined and discussed. If phobia and anxieties exist, the extensiveness of the case should be explained and relaxation techniques should be offered to ensure a comfortable and pain-free treatment experience. In addition, when a professional air of confidence, concern, and care is exhibited by the doctor, the patient's faith and interest can be gained. Once this rapport is established, the patient becomes far more receptive to accepting and entering a treatment program regardless of its difficulty and their apprehensions. The quality of treatment is inversely proportional to the level of stress experienced by the patient and the doctor during the procedure. Again, warning your patient about the potential for existing restorations to require future endodontic treatment is vital for continued patient trust.

Communication

Listen, Learn, and Record. Dentists are the professionals who must perform the tests, interpret the results, and design a treatment based on the information gathered. When the diagnosis is not evident, the dentist must turn to the patient for that one pinpointing clue. Sir William Osler, the famous English physician, once said, "Listen, listen, listen — for the patient is giving you the diagnosis." This statement is profound. The diagnostician must not only ask sufficient and leading questions to obtain as much information as possible but must also listen carefully to interpret the verbal response and its expressed meaning. Patients should be quoted verbatim in the chart, and their answers must become a permanent record for review.

Visual Examination

Direct examination of each tooth with some method of magnification (loupes or a microscope) is essential to locate fracture lines, decay, or defective restorations.

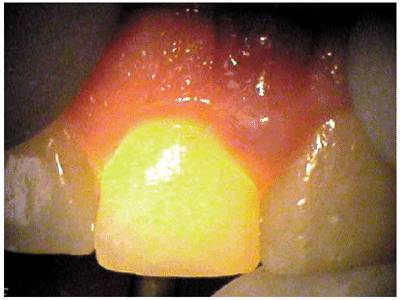

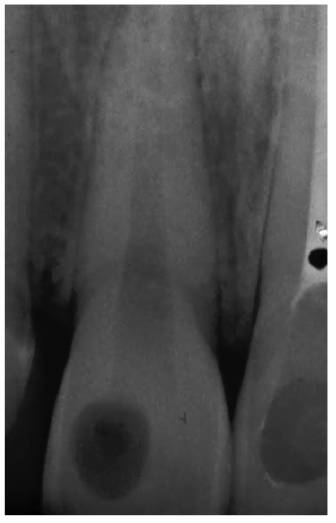

Transillumination via a fiber-optic light may be of great assistance in detecting color shifts in a crown (Figures 19-1A, and 19-1B). A tooth with a pink or reddish hue would more than likely indicate internal hemorrhage from a recent injury (Figure 19-2), a dental procedure (Figure 19-3), or gingival tissue hyperplasia that has invaded a coronal cavity produced by caries or resorption (Figures 19-4A, 19-4B, 19-4C, and 19-4D).

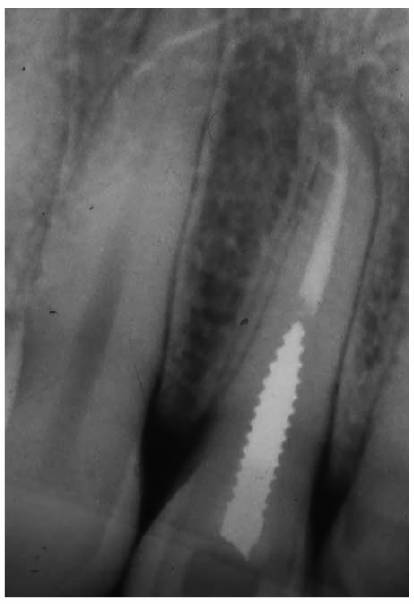

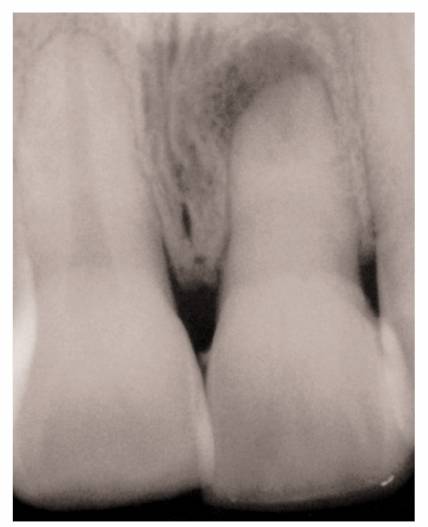

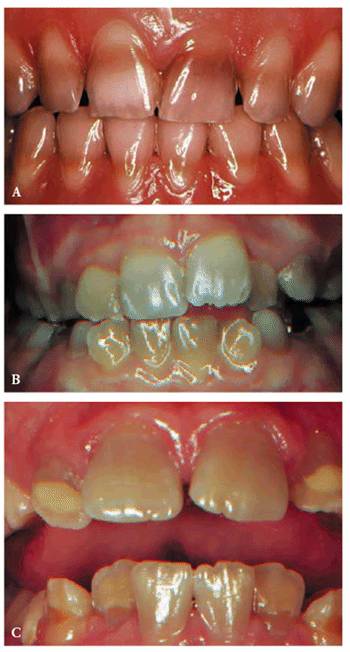

A gray, blue, or black color might indicate blood infiltrate hemostasis within the dentinal tubules and chamber, long-term necrotic tissue (Figure 19-5), or silver precipitants from certain root canal sealers and filling materials (Figures 19-6A, 19-6B, and 19-6C). A yellow or brown (Figures 19-7A, and 19-7B) unrestored crown often represents a physiologically calcified nonpathologic obliteration of the root chamber/ canal. Pharmacologically affected (ie, tetracycline-stained) teeth may vary in color from yellow to black (Figures 19-8A to C), and their drug fluorescence and etiology may be verified by using an ultraviolet or Woods black light.

The reader is referred to the chapter on bleaching as many of these discolorations can be reduced or eliminated by oxidizing techniques and agents without requiring endodontic intervention.

Teeth with vertical fractures have a diagnostic constant. The transilluminated light does not pass through the fracture line, but the crown beyond the fracture (Figures 19-9A and B) or the opposite cusp(s) (Figure 19-10) appears darker. Periodontal probing, cold testing, and a bite test will possibly assist in confirming the diagnosis of cracked tooth syndrome.

Figure 19-1A: Transillumination of a maxillary left central incisor with a necrotic pulp.

Figure 19-1B: Transillumination of the adjacent tooth with a vital pulp. Because there is active blood flow through the live pulp tissue, the tooth appears brighter to the fiber-optic light than the adjacent tooth with a necrotic pulp.

Figure 19-2: The maxillary central and lateral incisor teeth experienced a concussion injury and there was subsequent extravasation of blood causing the reddish hue.

Figure 19-3: One week following crown preparation, the tooth structure was red, signifying extravasation of blood and the need for pulp extirpation.

Figure 19-4A: Pink spot as a result of external resorption.

Figure 19-4B: Radiograph of the same tooth showing external resorption.

Figure 19-4C: Pink spot as a result of internal resorption.

Figure 19-4D: Radiograph of the same tooth showing internal resorption.

Figure 19-5: Discolored maxillary central incisors with necrotic pulps.

Figure 19-6A: Discoloration from silver-containing root canal cement.

Figure 19-6B: Gray color of crown from a post.

Figure 19-6C: Same radiograph as 19-6B. An unnecessary post that caused the discoloration.

Figure 19-7A: The crown of this maxillary central incisor discolored gradually over a 3-year period following a concussion injury. The complete fill-in of the pulp chamber with dentin is the cause of the yellowish brown hue. In the absence of periapical radiographic changes and clinical symptoms, endodontic therapy is not indicated.

Figure 19-7B: Radiograph of a similar maxillary central incisor 10 years after a concussion injury. The pulp chamber is filled in with dentin producing the discoloration. In this case, there was pulp death years after the discoloration appeared. Because the pulp canal was obliterated, a surgical approach was used to seal the apex.

Figure 19-8A to C: (A) Brown staining from Terramycin. (B) Gray staining from Acromycin. (C) Tan staining from Aureomycin.

Figure 19-9A and B: (A) View of a maxillary central incisor tooth with overhead lighting. No fracture is visible. (B) Transilluminated view of the same tooth revealing the fracture line.

Figure 19-10: Transillumination of a mandibular second molar. The fracture lines at the mesial and lingual grooves do not allow the light to pass through.

- on 01.11.2012 [endodontics]

- on 01.11.2012 [endodontics]

- on 01.11.2012 [endodontics]

- on 10.13.2011 [endodontics]

- on 12.15.2010 [endodontics]

- on 08.11.2010 [endodontics]

- Long Island College Hospital - [education]

- Faculty of Dental Medicine - H [education]

- The American Association of Or [organize]

- Summer Institute in Clinical D [organize]

- Academy of Osseointegration [organize]

- University of North Carolina a [education]

- American Orthodontic Society [article]

- American Equilibration Society [article]

- Niigata University - Japan [education]

- University of Buffalo [education]