ENDODONTICS AND ESTHETIC DENTISTRY(8)

PULPAL RESPONSE TO OPERATIVE PROCEDURES

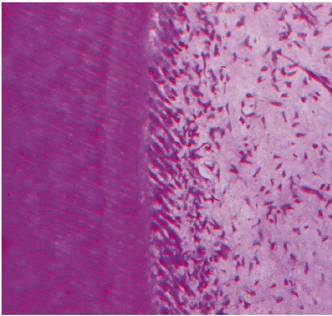

Following caries, the single most influencing factor on the health of the pulp (Figure 19-26) is the operator. Simply modifying traumatic operative techniques could easily prevent sequelae and reduce the eventual need for iatrogenically required endodontics.

A normal tooth, when cut, responds immediately to the dentinal injury. The involved tubules are vulnerable to the heat developed during the procedure, to the air during drying, and to any of the chemicals or materials used during the restorative procedures.

Figure 19-26: A vital healthy pulp with a typical pattern of palisading odontoblasts. (Photograph courtesy of Dr. Harold R. Stanley.)

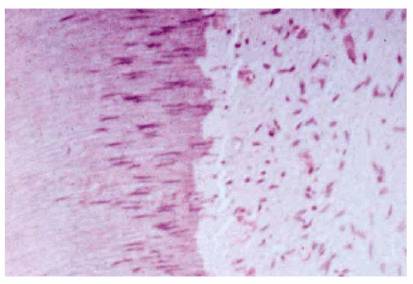

Regardless of the source, the odontoblasts will react. It is only a question of degree. With tooth reduction, the equation is simple: the higher the speed of the rotating instrument, the greater the heat generated, and the greater the pulpal damage. Common sense would suggest that in response to these predictable and undesirable insults, the surface of the tooth should be reduced with high speed, and the deepest excavation and final preparation should be achieved with low speed. Adjunctively, a coolant spray should accompany all cutting, and every effort should be made to eliminate air blasts. Not only has Langeland shown that 10 seconds of air is enough to displace odontoblastic nuclei (Figure 19-27) and present a definite hazard to the viability of the pulp,16 but

Figure 19-27: Aspiration of odontoblastic nuclei as a result of injury from cavity preparation.

For the above reasons, there is a definite advantage to using an alternative to the typical high-speed handpiece. Either air abrasion or a laser that cuts hard tissue, such as an erbium:YAG laser, can be much kinder to the pulp tissue.10 Although neither of these instruments can be used for a full-crown preparation, they may be ideal for initial cavity preparation, thereby negating potential pulp damage.

In addition, bleaching, rapid tooth movement, impression taking, temporization, and cementation are other aggressive procedures within the normal dental regimen that demand equal attention and caution.

The operator should select materials and agents that have relatively neutral pH values, create little or no heat during set, and control orthodontic forces within the physiologic tolerance of the periodontal ligament.

To ensure pulpal health and to avoid raising future diagnostic and treatment dilemmas, the pulp must be treated with the utmost care. In many situations, these problems may be avoided by careful evaluation prior to and during the restorative treatment. Examples of such situations are as follows:

1. When a tooth is exhibiting symptoms such as being exquisitely painful to cold liquids long after excavation of deep decay even with pulp protection/sedation and final restoration (Figure 19-28).

2. A patient cannot exert full biting pressure on a crown 6 to 9 months after cementation, yet the radiographs are negative (Figure 19-29).

Some postrestorative exacerbations are predisposing and unavoidable, particularly when dealing with heavily restored teeth. Such episodes of acute or chronic pulpal inflammation more often stem from a preexisting pulpal condition that has been aroused by what appeared to be a simple operative procedure. Although the healing potential of a healthy pulp following dental intervention has been well documented, the potential for complete repair has been known to decrease as the number of procedures are accumulated during a tooth's lifetime. Provided that there are no additional insults, a healthy pulp's survival with resolution of acute inflammation will usually take place within a few weeks. However, extending a patient's palliative treatment beyond that time frame is not only unjustified but also seriously threatens the patient/doctor relationship. Once that happens, further communications are diluted, and the patient usually leaves the practice. Rather, extirpation of the pulp followed by endodontic therapy should be considered early, and the patient should be warned that that might be the best treatment option if the symptoms do not resolve within a reasonable time.

Figure 19-28: Periodontally compromised maxillary central incisor that is painful to minor temperature changes 10 weeks after deep caries excavation and crown preparation.

Figure 19-29: Mandibular molar with a normal radiographic appearance. However, the patient avoids using the tooth because of pain when chewing 9 months after cementation of the crown.

- on 01.11.2012 [endodontics]

- on 01.11.2012 [endodontics]

- on 01.11.2012 [endodontics]

- on 10.13.2011 [endodontics]

- on 12.15.2010 [endodontics]

- on 08.11.2010 [endodontics]

- Long Island College Hospital - [education]

- Faculty of Dental Medicine - H [education]

- The American Association of Or [organize]

- Summer Institute in Clinical D [organize]

- Academy of Osseointegration [organize]

- University of North Carolina a [education]

- American Orthodontic Society [article]

- American Equilibration Society [article]

- Niigata University - Japan [education]

- University of Buffalo [education]