ENDODONTICS AND ESTHETIC DENTISTRY(9)

Pulpal Repair

Reparative or irregular dentin is deposited to form a protective barrier for the pulp tissue and is generally localized to the injury site. This abnormal dentin forms in response to intense and aggressive pulpal irritants that have reached the limit of pulp tolerance (eg, erosion, abrasion, caries, dentinal exposure by fracture, decay or mechanical tooth reduction, traumatic injury, caustic medicaments, and harmful filling materials).

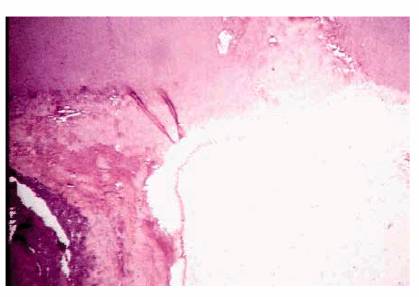

The histologic appearance of reparative dentin (Figure 19-30) demonstrates dentinal tubules that are irregular, tortuous, or even absent. The increased thickness of the total dentin is likely the reason for patients having decreased responses to cold stimuli as time passes following a dental procedure. Quantitatively, it is noted that the greater the degree of the "insult" caused by preparations and restorative materials, the greater the amount of reparative dentin that forms.

Although this calcified solid wall is considered beneficial and capable of resisting further episodes of irritation, this healing phenomenon decreases the ability of the tooth to respond to pulp testing at a later date.

Figure 19-30: Reparative dentin is deposited at specific sites as a result of injury (ie, caries, restorative procedures, attrition, or trauma).

Secondary Dentin

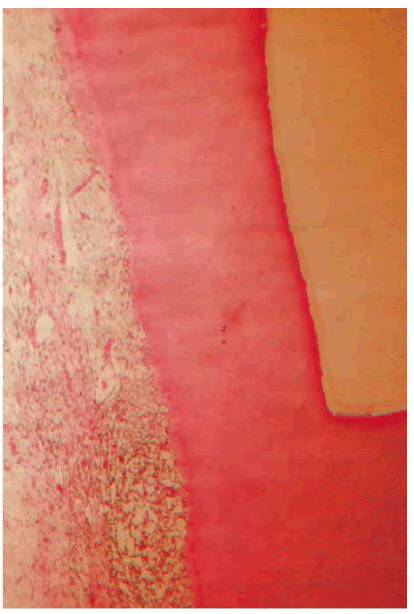

Histologically and physiologically, there is a difference between reparative and secondary dentin. Secondary dentin begins forming soon after the tooth erupts into occlusion and continues to form throughout the pulp's life. This tooth structure is deposited over the primary dentin (Figure 19-31) throughout the entire chamber and canal in response to stimuli within the limits of normal biologic function: mastication, light thermal changes, chemical irritants, and slight trauma. The newly deposited dentinal tubules are smaller, exhibit more curves, and form a protective barrier for the pulp as the size of the pulp cavity is reduced. Reparative dentin forms as a direct response to injury. Although the deposition is not uniform in thickness, this dystrophic calcification may completely occlude the canal, reduce the blood supply, necrose the tissue, and complicate the eventual endodontic therapy.

Figure 19-31: Secondary dentin represents the continuing slower circumpulpal deposition of dentin after root formation is complete.

ELECTIVE ENDODONTICS FOR PULPAL REASONS

Depth of Preparation/Remaining Dentin

According to Stanley and Swerdlow, "The most important single factor in determining pulpal response to a given stimulus is the remaining dentin thickness between the floor of the cavity preparation or the surface of a crown preparation and the pulp chamber."28 Studies have shown that a 2-mm dentin thickness between the floor of the cavity preparation and the pulp (Figure 19-32) will provide adequate insulation against the more traumatic thermogenic operative techniques in spite of intentional abuse and most restorative materials.23 Cavity or crown preparations cut with high speed (50-200,000 rpm), air water spray, and a light touch produced minimal pathologic alteration to healthy pulps when the remaining dentin was 2 mm or more. However, Stanley stated that "Although 2 mm of primary dentin between the floor of the cavity preparation and the pulp is usually a sufficient protective barrier against cutting techniques…the effluent of cements and self-curing resins can overcome this thickness of protection."27 To avoid such intrusions, calcium hydroxide lining materials capable of protecting the pulp tissue, when appropriately used, should be placed in all deep-seated cavity preparations prior to building a secondary protective base of cement.

Figure 19-32: Cavity preparation with 2 mm of remaining dentin between its floor and the pulp tissue. (Photograph courtesy of Dr. Harold R. Stanley.)

If the final restoration is a one-stage procedure (ie, amalgam or composite resin), then a dentin/pulpal floor protected with a calcium hydroxide dressing base can be permanently restored. The patient must be advised if there are risks involved. The records should reflect the risk condition and the discussion. The scenario differs with multistage restorations (ie, castings). If a tooth is compromised, the additional insults of impression, try-in, and cementation may exceed the pulp's ability to repair. Although judgmental, these teeth should be intentionally extirpated and endodontically treated. Success rates justify this prophylactic approach, and it is almost always unwarranted to chance discomfort, re-treatment, and repercussion.

If the requirements of the final restoration or the excavation of extensive caries result in less than 2 mm of remaining dentin, the expectation of a severe inflammatory reaction is greater. If a pink spot in the cavity or a blush on the tooth appears (Figures 19-33A, and 19-33B) during or after preparation, it is obvious that the 2-mm remaining dentin barrier has been violated. The probability of complete inflammatory reversibility and healing of a noticeably hemorrhagic pulp is minimal. Considering that additional procedures are required to finish the crown, elective endodontics should be instituted before continuing. If, at any time, a patient elects to forego endodontic therapy following your recommendations, the records must indicate that the option to extirpate was strongly suggested and refused.

Figure 19-33A: Pink crown preparation 1 week following instrumentation.

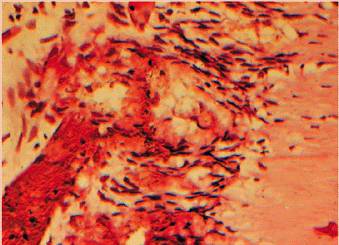

Figure 19-33B: Hemorrhagic pulp with extravasation of blood. (Photograph courtesy of Dr. Harold R. Stanley.)

This presents a moral issue as to whether a patient should be allowed to dictate the final treatment when the risk of failure is involved. The dentist must realize that he or she can always refuse to continue, provide palliative but temporary treatment to ensure comfort, and suggest that the patient see another dentist. If chosen, this decision, discussion, and referral must be recorded and witnessed. Irrespective of the remaining dentin thickness, the restoration has to be bacteria tight if the pulp is going to survive the insult. Care has to be taken to ensure the bacterial seal because if there is leakage, the bacteria will penetrate under the restoration and through the dentinal tubuli, initially cause pulpal irritation, and eventually cause pulpal necrosis if the leakage is not stopped.

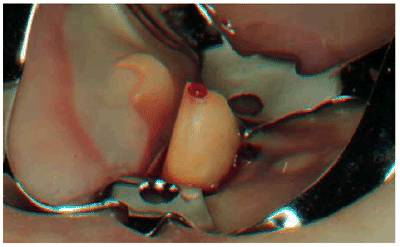

Pulp Capping

Direct pulp capping in special situations has been shown to be safe, effective, and predictable. The ability of the pulp to repair when a mechanical exposure has been dressed with calcium hydroxide is well documented. The odontoblastic layer, once stimulated, forms a matrix that leads to the bridging of new dentin. This is because if the pulp was accidentally exposed by a dental bur (Figure 19-34) or by traumatic injury, then only the surface will show reversible inflammatory changes. If the pulp exposure is under deep decay, then there is good likelihood that the inflammation has affected a large portion of the pulpal tissue and even caused partial necrosis. In a recently published study, the long-term success (over 10 years) of pulp capping of carious exposures was successful in only 13% of all cases evaluated.6 It is also important to remember that, as a rule, pulpitis is asymptomatic,8 so the patient might not have any history of pain even though there is a significant lesion in the pulpal chamber.

Figure 19-34: Pulp exposure during crown preparation. Pulp extirpation is indicated.

Because of the risk of leakage of bacteria into the pulp, direct pulp capping should be considered only with one-stage restorations (ie, amalgam or direct resin) and only when the patient is aware of the condition and the risk.

A thin calcium hydroxide mix of Dycal (DENTSPLY/Caulk,

Figure 19-35: Dentin bridge following pulp capping with mineral trioxide aggregate (ProRoot MTA). Note the thickness of the bridge and the palisading odontoblastic layer. (Photograph courtesy of Dr. Mahmoud Torabinejad.)

Recently, pulp capping with a technique of acid etching and bonding has been advocated. This concept was based on clinical observations but has few scientific data for support. Pameijer and Stanley studied the technique in a carefully controlled experiment on primates.22 Their results showed that pulp caps with acid etching and bonding agents produced 45% necrotic pulps, and only 25% of the specimens developed dentin bridge formation. Of the group pulp capped with calcium hydroxide, only 7% of the pulps were necrotic, and 82% of the teeth developed dentin bridge formation. Obviously, if you elect to pulp cap, calcium hydroxide and MTA are the materials of choice.

The poor long-term prognosis of pulp capping and the ease and assurance of endodontics certainly demand that the patient be offered the more predictable alternative of root canal therapy when a definite exposure is confronted. In teeth with pulp exposures for which multistage restorative procedures are contemplated (ie, inlays, crowns, bridge abutments), conventional root canal therapy is the treatment modality of choice. Performing the endodontics prior to the prosthetic delivery obviates the above-noted liabilities.

- on 01.11.2012 [endodontics]

- on 01.11.2012 [endodontics]

- on 01.11.2012 [endodontics]

- on 10.13.2011 [endodontics]

- on 12.15.2010 [endodontics]

- on 08.11.2010 [endodontics]

- Long Island College Hospital - [education]

- Faculty of Dental Medicine - H [education]

- The American Association of Or [organize]

- Summer Institute in Clinical D [organize]

- Academy of Osseointegration [organize]

- University of North Carolina a [education]

- American Orthodontic Society [article]

- American Equilibration Society [article]

- Niigata University - Japan [education]

- University of Buffalo [education]